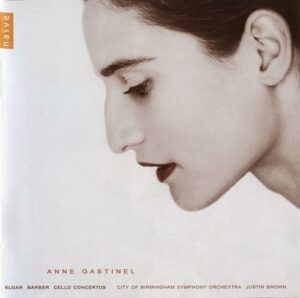

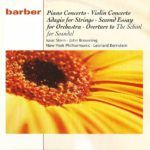

Pelo licença ao mano CDF para entrar em sua área, e postar este maravilhoso cd do Bernstein. Confesso que o baixei pensando no Copland, afinal, sabia que eles eram amigos, e também tinha curiosidade de ouvir o Adagio for Strings de Barber. Creio que em algum lugar o mano PQP comentou essa obra, e fiquei curioso de ouvi-la. E fiquei realmente encantado com sua beleza. Já tinha ouvido seu concerto para violino nas mãos jovens de Hilary Hahn, mas aqui temos o grande Isaac Stern tocando, aí a conversa é outra. Muitos consideram esta a melhor gravação deste concerto. Deixa-se a imaturidade de lado para entrar a experiência e exuberância de um dos grandes violinistas do século XX.

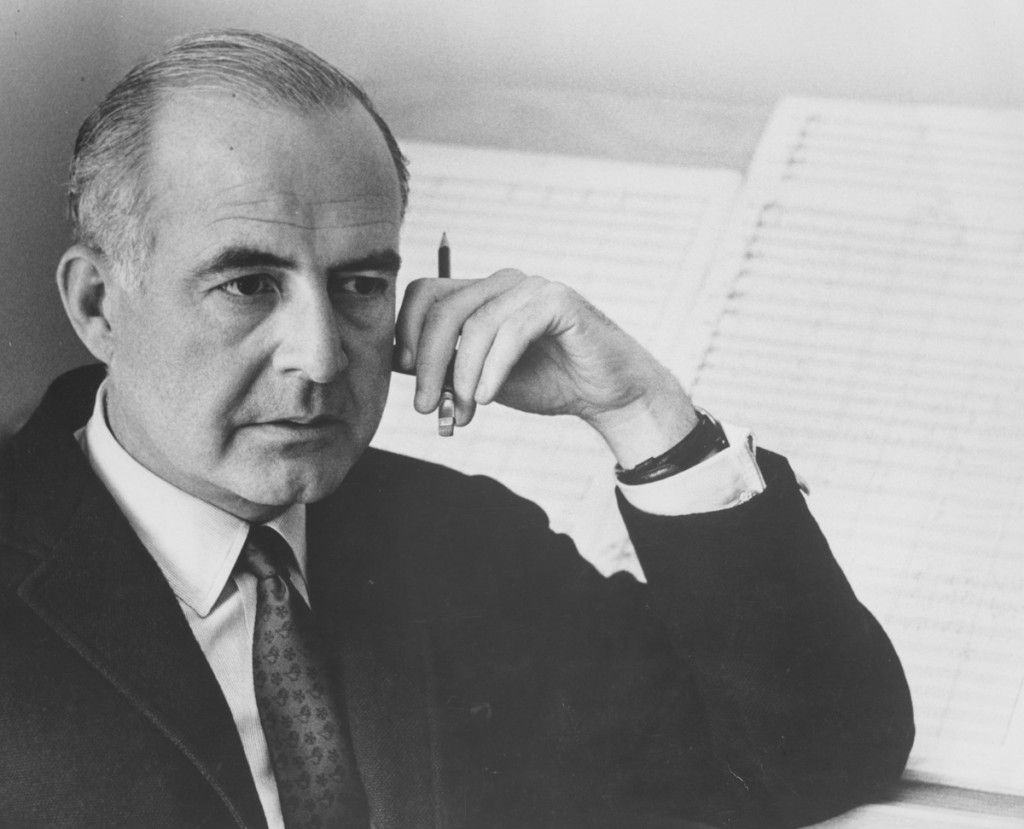

Com relação a William Schuman, reconheço minha total ignorância e fui atrás de maiores informações, no fantástico New Groove Dictionary:

At the age of 16 Schuman wrote his first piece, a tango, and widened his practical experience by taking up various instruments and organizing and performing in jazz bands. He wrote many popular songs to lyrics by Edward B. Marks and Frank Loesser, including the latter’s first published song, In Love with a Memory of You. After hearing Toscanini conduct the New York PO on 4 April 1930 Schuman abruptly left the School of Commerce of New York University, where he had been studying for two years, and began private harmony lessons with Max Persin and, in 1931, counterpoint lessons with Charles Haubiel in New York.

While Schuman continued to write popular music until 1934, his study and composing veered increasingly towards concert music. He took summer courses with Bernard Wagenaar and Adolf Schmid at the Juilliard School (1932, 1933), spent a summer in the conducting programme at the Salzburg Mozarteum (1935), and in 1933 enrolled in Columbia University Teachers College (BS 1935, MA 1937). During 1932–5 Schuman had begun composing seriously, and after hearing Roy Harris’s Symphony 1933 he studied with Harris at Juilliard (summer 1936) and then privately (until 1938); Harris remained for some years an important influence on Schuman’s orchestral music.

In 1938 Schuman won an American composition contest (in support of Republican Spain) with his Second Symphony. On the jury was Aaron Copland, who brought the work to the attention of Koussevitzky. Koussevitzky became a champion of Schuman’s compositions, conducting the Second Symphony with the Boston SO in 1939, and first performances of the American Festival Overture (1939), the Symphony no.3 (1941, awarded the first New York Music Critics’ Circle Award), A Free Song (1943, awarded the first Pulitzer Prize in music), and the Symphony for Strings (1943). The public and critical success of the Symphony no.3 established Schuman as a leading American composer and since that time his music has been widely performed. He remains among the most honoured figures in American music, having received 28 honorary degrees, 2 consecutive Guggenheim fellowships (1939–41), membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1946) and later the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1973), the first Brandeis University Creative Arts Award in music (1957), the Horblit Award from the Boston SO and Harvard University (1980), the gold medal from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1982) and a second, special Pulitzer prize (1985). Credendum (1955) was the first composition to be commissioned by the US government. In 1981 Columbia University established the William Schuman Award, a $50,000 prize to a composer for lifetime achievement; Schuman himself was the first recipient.

Schuman’s work as a teacher and administrator has had wide and lasting influence. At Sarah Lawrence College, where he taught from 1935 to 1945, he initiated an approach to general arts instruction aiming at students’ self-discovery of the nature of the creative process; he went on to evolve a similar approach to the teaching of other subjects, including composition. Schuman also conducted the chorus at Sarah Lawrence (1939–45), commissioning and composing works for women’s voices. In 1945, after leaving Sarah Lawrence for a three-year term as director of publications at G. Schirmer, Schuman was invited to become president of the Juilliard School. He left the Schirmer position (though he remained as a special editorial consultant until 1952), and began an extensive reorganization of the School: he merged the Institute of Musical Art with the Juilliard Graduate School to form the Juilliard School of Music, founded the Juilliard String Quartet (which became the model for many quartets-in-residence at American colleges), revived the opera theatre, added a dance division, and, most importantly, instituted the ‘Literature and Materials of Music’ curricular programme, which fused theory and history into a single coherent four-year course with the music itself as the basis for study. An exposition of his approach to music education appeared as The Juilliard Report (1953). Schuman also invited a number of distinguished composers to join the faculty, among them Bergsma, R.F. Goldman, Peter Mennin, Norman Lloyd, Vincent Persichetti, Robert Starer, Robert Ward and Hugo Weisgall.

In 1962 Schuman was made president of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, a position which gave him considerable influence in the administration of the arts and one which he exercised in a characteristically imaginative and forceful manner. He encouraged the commissioning and performing of American works, and the importance he placed on the centre’s service to urban communities led to the Lincoln Center Student Program, which instituted concerts in schools and opened the centre’s halls for young people’s concerts. He founded the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Film Society and a summer series of special musical events. He fought a long and successful battle to have the Juilliard School housed in Lincoln Center and to add a drama division to its offerings. At the end of 1969 Schuman left his post at Lincoln Center to devote himself to composition, but he has continued to champion the cause of the arts as a public speaker and as an adviser to numerous organizations, including the Koussevitzky Foundation, the Naumburg Foundation and the Charles Ives Society. He was chairman of the MacDowell Colony (1974–7, 1980–83) and became honorary chairman in 1984; he was the founding chairman of the Norlin Foundation (1975–85). He received the Gold Baton Award of the American Symphony Orchestra League (1985), the National Medal of Arts (1987) and the Kennedy Center Honors (1989). Schuman continued to compose despite a painful inherited bone disease. He maintained his legendary personal charm and gifts as a public speaker to the end.

Aliás, quando vi o sobrenome, sem o prenome, fiquei imaginando qual seria o critério do produtor,e do próprio Lenny, de inserir Robert Schumann entre compositores norte americanos do século XX.

O CD ainda traz Charles Ives e Aaron Copland, motivo inicial de meu interesse por este cd. E novamente evoco o trio inglês Emerson, Lake & Palmer, fás confessos deste compositor, e de quem constantemente gravaram obras (Rodeo, e esta mesma Fanfare for a Common Man), entre outras.

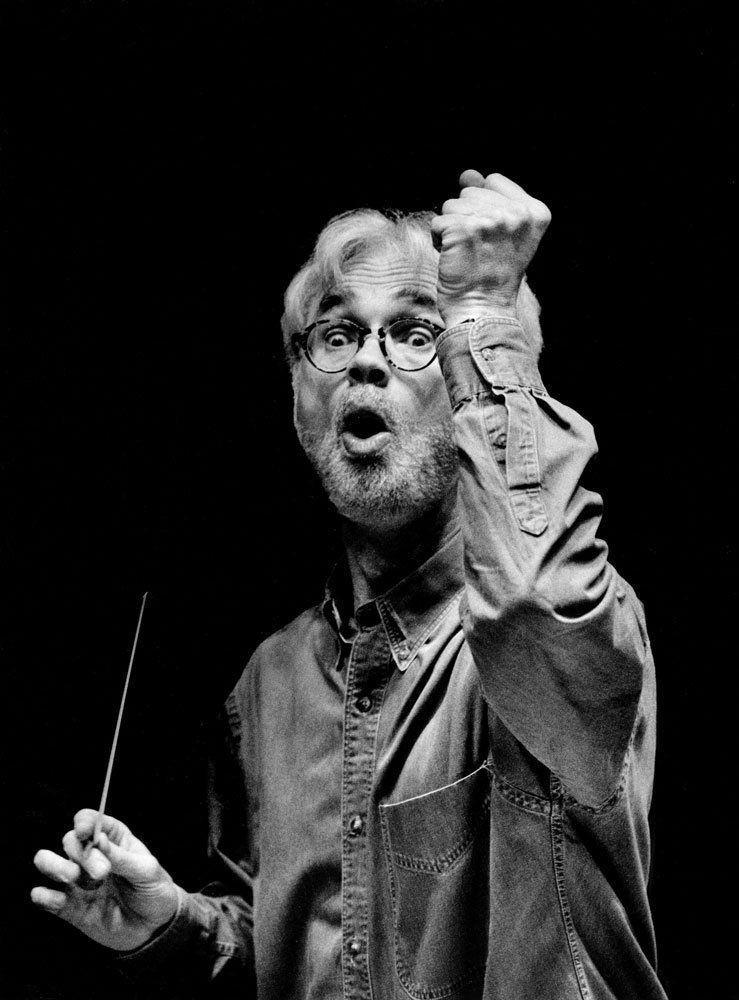

Um grande cd, com um dos grandes maestros do século XX, e claro, grande especialista neste repertório.

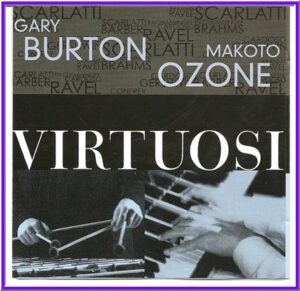

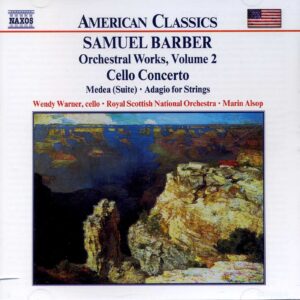

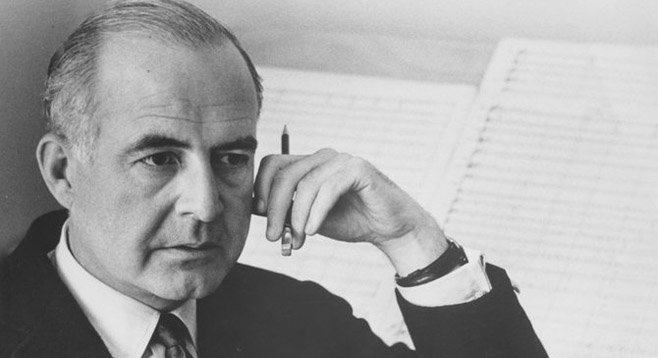

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

1 – Adagio for Strings

2 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 14 – Allegro

3 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 14 – Andante

4 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, op. 14 – Presto in moto

Isaac Stern – Violin

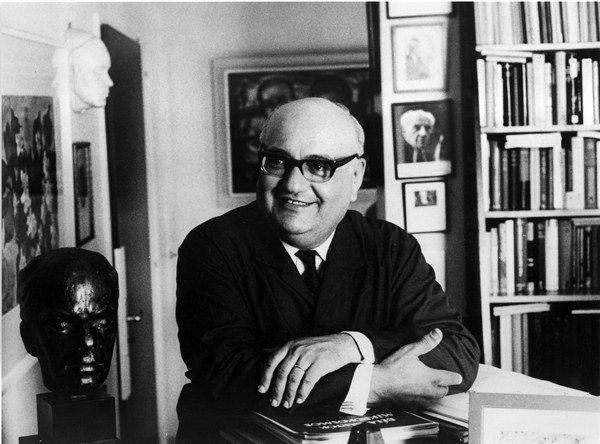

William Schuman (1910-1992)

5 – To Thee Old Cause (Evocation for Oboe, Brass, Timpani, Piano & Strings)

Harold Gomberg – Oboe

6 – In Praise of Shahn (Canticle for Orchestra) – Vigoroso

7 – In Praise of Shahn (Canticle for Orchestra) – Lento (bar 185)

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

8 – The Unanswered Question

William Vacchiano – Trumpet

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

9 – Fanfare for a Common Man (Version from Symphony nº3) – Molto Liberato

New York Philharmonic

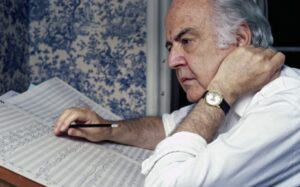

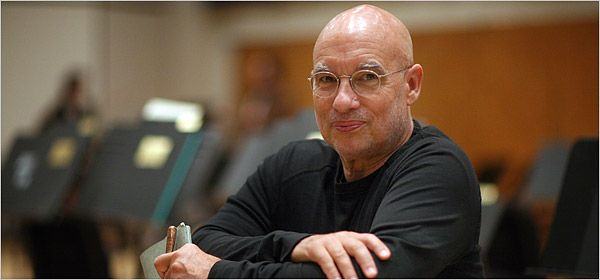

Leonard Bernstein – Conductor

BAIXE AQUI – DOWNLOAD HERE

FDP Bach

IM-PER-DÍ-VEL !!! (Volume bem alto, por favor).

IM-PER-DÍ-VEL !!! (Volume bem alto, por favor).