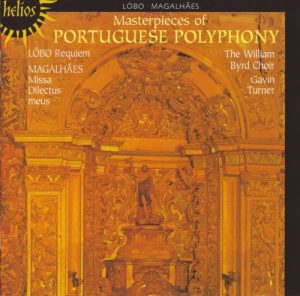

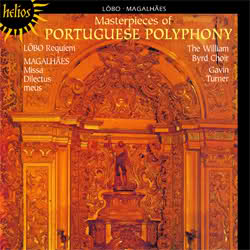

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony

The William Byrd Choir

Há certa ironia no fato de que a música portuguesa tenha tido sua melhor fase justamente nos anos da dominação espanhola (1580 a 1640). No entanto, apesar de Felipe II da Espanha ter patrocinado generosamente os músicos de seu novo domínio, foi a família ducal dos Bragança – o Cardeal Henrique e sobretudo o duque João, que seria o rei Dom João IV depois da restauração – quem mais encorajou os mestres músicos que são a glória da música sacra portuguesa na primeira metade do século 17.

Duarte Lôbo, Filipe de Magalhães, o frade carmelita Manuel Cardoso, Lopes Morago, Brito, Francisco Martins e o monge Pedro de Cristo foram a figuras mais representativas nesse período que se inicia quando Palestrina vivia seus últimos dias e termina algum tempo depois da morte de Monteverdi.

Seu estilo é fortemente conservador, sendo um genuíno desenvolvimento direto daquilo que chamamos hoje de “polifonia renascentista”; levaram adiante a tradição de Morales, de Palestrina, de Guerrero (muito querido pelos compositores portugueses posteriores) e de [Tomás Luis de] Victoria. Seus contemporâneos espanhóis são Vivanco, López de Velasco, Carlos Patiño, entre outros. Foi somente mais tarde, em meados do século 17, que João Lourenço Rebelo, Pedro Vaz Rego e Diogo Dias Melgás “alncançaram” as gerações “barrocas” espanholas que se iniciam com Mateo Romero e com Cererols, e chegam até José de Torres y Martínez Bravo e a Francisco Valls.

O repertório de um coro de catedral portuguesa na década de 1630 é tipificado pelo inventário de 1635 encontrado em Coimbra. Ele enumera livros de motetos e de missas de Victoria, missas e magnificats de Duarte Lôbo e de Magalhães, e missas de Cardoso. Os espanhóis se encontram representados aí por livros de missas de Alonso Lobo, Juan Esquivel e dos mestres mais antigos Morales e Guerrero. Também se encontravam os livros de música para Vésperas publicados por Navarro e Esquivel, junto com música de Philippe Rogier, nascido nos Países Baixos e mestre da Capilla Flamenca em Madri.

Quer dizer: um repertório fortemente ibérico. De fora, nem mesmo Palestrina está incluído, embora sua música fosse bem conhecida e usada desde há muito na Espanha e em Portugal.

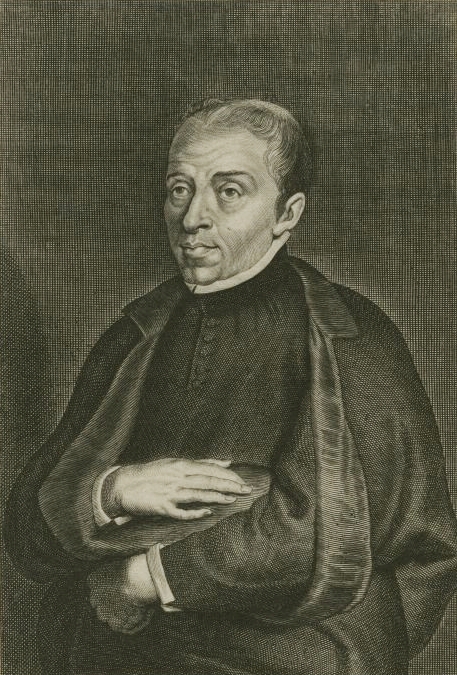

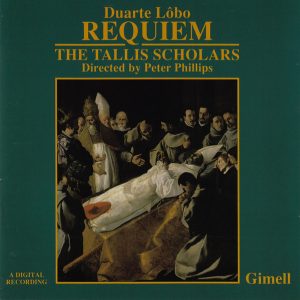

DUARTE LÔBO (que não deve ser confundido com o espanhol Alonso Lobo, e também conhecido pela forma latinizada Eduardus Lupus) foi o compositor português mais conhecido em sua época; suas obras eram bastante executadas em seu próprio país e nos Países Baixos espanhóis, bem como no México e Guatemala. Nasceu em 1565 ou 67, e morreu em 1646. Lôbo estudou com Manuel Mendes no famoso Colégio da Claustra de Évora, cidade em que também foi cantor e por um breve período diretor do coro da catedral. Mudou-se para Lisboa para encarregar-se da música no Hospital Real, e em 1594 se tornou mestre de capela na catedral dessa capital, onde também lecionou no Colégio da Claustra, mantendo esses vários cargos, respeitadíssimo, até a sua aposentadoria, quando passou a dirigir a música no Seminário de São Bartolomeu até sua morte.

As obras de Lôbo que sobreviveram incluem suas edições de textos e de cantochão para o Ofício dos Mortos (Lisboa, 1603) e o Processional de Lisboa (1607), e sua aprovação aparece em diversas publicações de métodos de cantochão e num Passionário (coleção de cantos para a Semana Santa) de 1595. Suas próprias composições, além disso, foram belamente impressas – na verdade até suntuosamente – pela firma Plantin de Antuérpia.

Os dezesseis arranjos de Lôbo para o Magnificat foram publicados em 1605. São concisos e breves, e portanto totalmente adequados para os serviços regulares das Vésperas. Em 1621 e 1639 vieram à luz os livros de missas. Estas vão de curtas e simples até obras elaboradas e imponentes para cinco, seix e oito vozes. Os dois missais se encerram com uma Missa pro Defunctis e alguns motetos fúnebres. As missas são treze, sem contar os arranjos do Requiem.

A Missa de Requiem de 1621 é a oito vozes, a de 1639 é a seis, tendo esta uma característica incomum na época que é a alternância de cantochão e polifonia no Dies Irae. A de 1621 não é para dois coros separados, embora ocorram momentos antifonais entre os dois grupos. As vozes são duas de soprano, duas de contralto, duas de tenor e duas de baixo. A edição de 1621 incluir as entoações, incipits e versos em cantochão, e com isso se pode ver que a polifonia é estreitamente relacionada às antigas melodias dos cantos, que são citadas ou parafraseadas com frequência.

Em momentos breves porém frequentes, Lobo raleia sua textura de oito vozes; sua harmonia é bem simples porém muito firme, com linhas de baixo direcionadas com decisão. O efeito geral termina sendo de homofonia, mas encontramos uma abordagem contrapontística bastante viva no gradual e no ofertório. No verso ‘In memoria’ do gradual encontramos um trio livremente fluente, mas no restante são empregadas todas as oito vozes. Os movimentos inicial e final são extremamente simples: temos aí o tipo de música que parece nada quando vista no papel, mas quando executada mostra grande dignidade e atmosfera. A música é exatamente o que Lôbo, sacerdote e compositor por profissão, pretendia que fosse: totalmente adequada à Missa de Réquiem – os solenes ritos funerais ou memoriais da Igreja Católica.

A maior parte da edições da Missa de Réquiem nos séculos 16 e 17 traziam em anexo um ou mais motetos apropriados para funerais, e nesse sentido esta gravação traz Audivi vocem de caelo, uma obra a seis vozes que conclui o Liber Missarum de Lôbo publicado em 1621.

FILIPE DE MAGALHÃES, como seu contemporâneo Lôbo, foi aluno e corista em Évora, tendo cantado no coro da catedral e no Colégio da Claustra. Aí Magalhães se tornou o aluno predileto de Manuel Mendes, e em 1605 herdou toda a coleção musical de seu antigo professor. Tendo se mudado para Lisboa para ser cantor na Capela Real, tornou-se seu mestre de capela em 1623. Aposentou-se em 1641, um ano depois da Restauração em que o Duque João de Bragança tornou-se rei. Muitas de suas obras devem ter sido perdidas no grande terremoto de 1755; sabemos de diversas delas, inclusive uma missa a oito vozes, pelos catálogos da grande biblioteca musical de Dom João IV.

Ao contrário de Duarte Lôbo, Magalhães teve dois volumes de sua música impressos em Lisboa, e não em Antuérpia. A qualidade dos tipos e da impressão são pobres em comparação com os livros de Lôbo editados por Plantin, mas a música em si apresenta a alta qualidade e expressividade que levaram alguns escritores modernos a aclamar Magalhães como o maior dos compositores de Portugal.

Em 1636 Magalhães publicou seu volume de Magnificats, e seu Missarum Liber também vem claramente datado de 1636 na página de rosto. São esses dois livros que contêm a maior parte da música de Magalhães que chegou até nós. Encontramos aí sete missas para quatro ou cinco vozes, algumas das quais com um elaborado segundo arranjo do Agnus Dei. Curiosamente, as palavras finais dona nobis pacem [‘dá-nos a paz’] nunca aparecem nessas obras, mesmo quando existe um tal segundo Agnus Dei.

Por outro lado, todas as missas possuem dois movimentos claramente separados para o Christe Eleison, no que são similares a todas as outras missas compostas em Portugal nesse período. Não é nem um pouco claro se isso indica a possibilidade de alternância com cantochão, inclusive porque lá onde isso seria mais provável – no Réquiem baseado em cantochão – somos pegos de surpresa por apenas um Christe.

Sua Missa pro Defunctis gravada aqui é para seis vozes e é seguida pelo altamente expressivo moteto a seis vozes ‘Comissa mea pavesco’ que conclui o volume [presente também no CD Masters of the Royal Chapel, postado em 28/06].

O Ordinário da Missa executada nesta gravação é uma continuação típica da tradição de Palestrina e de Victoria, do final do século 16. A Missa Dilectus Meus foi baseada em um moteto ainda não encontrado. Está escrita para coro a cinco vozes, o soprano dividido (SSATB). Essa divisão de vozes é usada completa a maior parte do tempo, mas no Crucifixus do Credo é reduzida a SSAT, e no Benedictus a SAT [ambos sem baixo]. O Hosanna é em compasso ternário.

O segundo Agnus Dei [ver acima] é escrito para seis vozes, agora com divisão também nos altos [SSAATB]. A voz do tenor segue a parte do primeiro soprano em um cânon à oitava estrito. A música flui em um estilo polifônico sereno e efetivo, um belo exemplo do conservador stile antico praticado em Portugal.

A gravação se conclui com o moteto fúnebre Comissa mea pavesco, uma obra magistral, de uma escrita confiante, segura na sua sucessão de temas elaborados sem pressa, com um espírito penitencial tocante porém cheio de dignidade.

(Bruno Turner, 1986 – extraído do encarte. Traduzido do inglês e do alemão pelo Prof. Ralf Rickli <[email protected]> especialmente para esta postagem. Não tem preço!!)

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony: The William Byrd Choir

Duarte Lôbo (Portugal, c1565-1646; Latinized as Eduardus Lupus)

01. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 1: Introitus. Requiem aeternam

02. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 2: Kyrie

03. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 3: Graduale. Requiem aeternam

04. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 4: Offertorium. Domine, Jesu Christe

05. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 5: Sanctus

06. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 6: Agnus Dei

07. Missa Pro defunctis ‘Requiem’ – Movement 7: Communio. Lux aeterna

08. Audivi vocem de caelo

Filipe de Magalhães (Portugal, c1571-1652)

09. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 1: Kyrie

10. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 2: Gloria

11. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 3: Credo

12. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 4: Sanctus

13. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 5: Benedictus

14. Missa Dilectus meus – Movement 6: Agnus Dei

15. Commissa mea pavesco

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony: The William Byrd Choir – 2005

The William Byrd Choir

Director: Gavin Turner

Recorded in All Hallows, Gospel Oak, London, on 2 & 4 June 1986

Uma gravação patrocinada pela The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation em comemoração ao 600º aniversário do Tratado de Windsor, entre Inglaterra e Portugal.

BAIXE AQUI – DOWNLOAD HERE (com encarte)

MP3 320 kbps – 139,5 MB – 59 min

powered by iTunes 12.1.0

Boa audição.

Avicenna

Foi casual a data desta postagem se dar próxima ao Dia de Finados. Mas o que interessa é a qualidade da música de Duarte Lôbo e o incrível trabalho do Tallis. De forma paradoxal, os renascentistas espanhóis e portugueses criaram uma música religiosa sutil e discreta, mas também muito envolvente, intensa e profunda. Essa música de Réquiem portuguesa renascentista tem muito disso. Quase tudo de concentra nos acordes bonitos. Há a polifonia, claro, mas a ideia parece ser a de criar uma série de acordes bonitos. E aqui eles são lindos. Claro que o Tallis Scholars é fantástico e capricha demais. O que torna essa música ainda mais impressionante é a rotatividade harmônica. As partes internas se movem mais rapidamente do que as externas, criando um contraste entre eternidade e tumulto secular. O som é absolutamente incrível. As linhas vocais fluem, caindo em acordes que podem ser poderosos, delicados, às vezes alegres. É esplêndido. Em nenhum lugar isso é mais evidente do que no Introitus e no Kyrie (faixas um e dois). Quando a gente acha que virá uma grande tristeza, as vozes caem em outro acorde que nos faz sorrir. A Missa Missa Vox Clamantis também é boa.

Foi casual a data desta postagem se dar próxima ao Dia de Finados. Mas o que interessa é a qualidade da música de Duarte Lôbo e o incrível trabalho do Tallis. De forma paradoxal, os renascentistas espanhóis e portugueses criaram uma música religiosa sutil e discreta, mas também muito envolvente, intensa e profunda. Essa música de Réquiem portuguesa renascentista tem muito disso. Quase tudo de concentra nos acordes bonitos. Há a polifonia, claro, mas a ideia parece ser a de criar uma série de acordes bonitos. E aqui eles são lindos. Claro que o Tallis Scholars é fantástico e capricha demais. O que torna essa música ainda mais impressionante é a rotatividade harmônica. As partes internas se movem mais rapidamente do que as externas, criando um contraste entre eternidade e tumulto secular. O som é absolutamente incrível. As linhas vocais fluem, caindo em acordes que podem ser poderosos, delicados, às vezes alegres. É esplêndido. Em nenhum lugar isso é mais evidente do que no Introitus e no Kyrie (faixas um e dois). Quando a gente acha que virá uma grande tristeza, as vozes caem em outro acorde que nos faz sorrir. A Missa Missa Vox Clamantis também é boa.