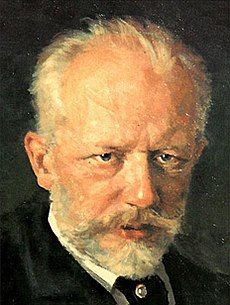

“After Tchaikovsky’s qualified success with The Sleeping Beauty, in February 1891 he was invited to compose the music for a new ballet. The scenario was based on Alexandre Dumas père’s adaptation of a story by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann, Nussknacker und Mausekönig. From the outset, The Nutcracker had its critics, none more trenchant than the composer himself. He wrote to his beloved nephew, Vladimir (Bob) Davydov on 7 July: ‘…I finished the sketches of the ballet yesterday. You will remember that I boasted to you when you were here that I could finish the ballet in five days, but I have scarcely finished it in a fortnight. No, the old man is breaking up … he loses bit by bit the capacity to do anything at all. The ballet is infinitely worse than Sleeping Beauty – so much is certain … If I arrive at the conclusion that I can no longer furnish my musical table with anything but warmed up fare, I will give up composing altogether.’

“After Tchaikovsky’s qualified success with The Sleeping Beauty, in February 1891 he was invited to compose the music for a new ballet. The scenario was based on Alexandre Dumas père’s adaptation of a story by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann, Nussknacker und Mausekönig. From the outset, The Nutcracker had its critics, none more trenchant than the composer himself. He wrote to his beloved nephew, Vladimir (Bob) Davydov on 7 July: ‘…I finished the sketches of the ballet yesterday. You will remember that I boasted to you when you were here that I could finish the ballet in five days, but I have scarcely finished it in a fortnight. No, the old man is breaking up … he loses bit by bit the capacity to do anything at all. The ballet is infinitely worse than Sleeping Beauty – so much is certain … If I arrive at the conclusion that I can no longer furnish my musical table with anything but warmed up fare, I will give up composing altogether.’

At its St. Petersburg première on [6 December] 18 December 1892 The Nutcracker formed half of a double bill with the darker operatic component, Iolanta, generally thought superior. Posterity has reversed this judgement. It is true that hardly any story survives in the ballet’s voyage from the (mimed) semi-reality of an idealized family Christmas to the land of eternal sweetmeats (and nothing but virtuoso dancing). Yet the score itself is brilliantly alive with no hint of time-serving tinsel. Tchaikovsky’s exploitation of his unmatched gift for melody was never more audacious.

The miniature overture opening the work sets the fairy mood by employing only the orchestra’s upper registers. The first act is divided into two scenes. It is Christmas Eve and little Clara is playing with her toys. At midnight they come to life. Led by the Nutcracker, her special present, they overwhelm some marauding mice, after which he is transformed into a Prince. Clara and her Prince travel through a snowy landscape where they are greeted by waltzing snowflakes. Ivanov’s original choreography, in which the dancers evoked the movements of windswept snow, was much admired by the cognoscenti who climbed up to the cheaper seats in order to appreciate the patterns created.

In Act 2 the Sugar Plum Fairy and the people of the Land of Sweets proffer a lavish gala of character dances. There follows a magnificent pas de deux for the Prince and the Sugar Plum Fairy, the latter’s own variation realising the composer’s desire to showcase the celesta, a new instrument he had heard in Paris. Its unique timbre is here famously complemented by little downward swoops from the bass clarinet. Elsewhere Tchaikovsky incorporates several children’s instruments including a rattle, pop-gun, toy trumpet and

miniature drum. After the festivities Clara wakes up under the Christmas tree, the Nutcracker toy in her arms, although, in some versions she rides off with her Nutcracker Prince as if the dream has happened in reality q.v. Hoffmann’s original story.

Radical modern interpretations include Mark Morris’s The Hard Nut (1991), set in the Swinging Sixties but faithful to the original score, and Donald Byrd’s Harlem Nutcracker (1996), danced to Duke Ellington’s jazz adaptation and set in an African-American household where Clara, the little girl, has become clan matriarch. That Tchaikovsky’s invention should present such riches to plunder, given the slight, somewhat incongruous scenario with which he had to work, says much about the nature of his genius.”

C David Gutman, 2010

CD 16

01. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – a. Miniature Overture

02. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – b. Act I; N.1 – The Decoration Of The Christmas Tree

03. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – c. Act I; N.2 – March

04. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – d. Act I; N.3 – Children’s Galop & Entry Of The Parents

05. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – e. Act I; N.4 – Arrival Of Drosselmeyer

06. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – f. Act I; N.5 – Grandfather’s Dance

07. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – g. Act I; N.6 – Scene. Clara And The Nutcracker

08. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – h. Act I; N.7 – Scene. The Battle

09. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – i. Act I; N.8 – Scene. In The Pine Forest

10. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – j. Act I; N.9 – Waltz Of The Snowflakes

11. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – k. Act II; N.10 – Scene. The Kingdom Of Sweets

12. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – l. Act II; N.11 – Scene. Clara And The Prince

13. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – m. Act II; N.12-a – Divertissement. Chocolate–Spanish Dance

14. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – n. Act II; N.12-b – Divertissement. Coffee–Arabian Dance

15. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – o. Act II; N.12-c – Divertissement. Tea–Chinese Dance

16. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – p. Act II; N.12-d – Divertissement. Trepak–Russian Dance

17. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – q. Act II; N.12-e – Divertissement. Dance Of The Reed Pipes

18. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – r. Act II; N.12-f – Divertissment. Mother Gigogne

19. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – s. Act II; N.13 – Waltz Of The Flowers

CD 17

01. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – t. Act II; N.14 – Pas de Deux

02. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – u. Act II; N.14-a – Pas de Deux–Variation I. Tarantella

03. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – v. Act II; N.14-b – Pas de Deux–Variation II. Dance Of The Sugar-Plum Fairy

04. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – w. Act II; N.14-c – Pas de Deux–Coda

05. The Nutcracker, Op.71 – x. Act II; No.15 – Final Waltz & Apotheosis

06. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op.55 – I. Elégie

07. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op.55 – II. Valse mélancolique

08. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op.55 – III. Scherzo

09. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op.55 – IV. Thème et Variations

10. Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G major, ‘Mozartiana’, Op.61 – I. Gigue

11. Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G major, ‘Mozartiana’, Op.61 – II. Menuet

12. Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G major, ‘Mozartiana’, Op.61 – III. Preghiera

13. Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G major, ‘Mozartiana’, Op.61 – IV. Thème et Variations

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Ernest Ansermet – Conductor

CD 16 – BAIXE AQUI – DOWNLOAD HERE

CD 17 – BAIXE AQUI – DOWNLOAD HERE

Na década de 50-60, em plena guerra fria, a competição entre URSS e EUA não ficava apenas no plano político e tecnológico. Nas artes, era muito comum uma troca de provocações indiretas (ou mesmo diretas), à superioridade estética de entidades ou artistas de cada um dos lados. E, por conta da dificuldade de acesso ao confronto direto (os artistas não podiam circular livremente na URSS), muitos desses confrontos acabavam ficando no plano imaginativo. Um deles, na música, era a propaganda que se fazia da superioridade sonora da Filarmônica de Leningrado e seu mítico maestro, Evgeny Mravinsky. Foram necessários anos de negociações até que o Kremlin permitisse uma tournée pela Europa. A primeira, em 1956, resultou numa gravação monaural primorosa das Sinfonias 4, 5 e 6 de Tchaikovsky, pela DG, em que toda a emoção do ineditismo (tanto de um lado quanto de outro) fica evidente. Quatro anos depois, Elsa Schiller, produtora da DG, conseguiu, não sem muito esforço, que o grupo voltasse para gravar em estéreo as mesmas obras, já que a primeira vez impressionou profundamente os europeus. E realmente, esta é uma leitura acima de qualquer crítica. Além da intimidade evidente dos músicos com estas obras, a precisão e sensibilidade de Mravinsky, um dos maestros mais elegantes que já subiram ao pódio, torna esta leitura indispensável em todos os sentidos. Soma-se a isso um aspecto levantado por Norman Lebrecht, que a torna ainda mais fascinante: sob pressão política, os registros evidenciam a tragédia do finale da Patética com profundeza ímpar, e a marcha bélica do terceiro movimento com uma esperança aterradora. É ver pra crer.

Na década de 50-60, em plena guerra fria, a competição entre URSS e EUA não ficava apenas no plano político e tecnológico. Nas artes, era muito comum uma troca de provocações indiretas (ou mesmo diretas), à superioridade estética de entidades ou artistas de cada um dos lados. E, por conta da dificuldade de acesso ao confronto direto (os artistas não podiam circular livremente na URSS), muitos desses confrontos acabavam ficando no plano imaginativo. Um deles, na música, era a propaganda que se fazia da superioridade sonora da Filarmônica de Leningrado e seu mítico maestro, Evgeny Mravinsky. Foram necessários anos de negociações até que o Kremlin permitisse uma tournée pela Europa. A primeira, em 1956, resultou numa gravação monaural primorosa das Sinfonias 4, 5 e 6 de Tchaikovsky, pela DG, em que toda a emoção do ineditismo (tanto de um lado quanto de outro) fica evidente. Quatro anos depois, Elsa Schiller, produtora da DG, conseguiu, não sem muito esforço, que o grupo voltasse para gravar em estéreo as mesmas obras, já que a primeira vez impressionou profundamente os europeus. E realmente, esta é uma leitura acima de qualquer crítica. Além da intimidade evidente dos músicos com estas obras, a precisão e sensibilidade de Mravinsky, um dos maestros mais elegantes que já subiram ao pódio, torna esta leitura indispensável em todos os sentidos. Soma-se a isso um aspecto levantado por Norman Lebrecht, que a torna ainda mais fascinante: sob pressão política, os registros evidenciam a tragédia do finale da Patética com profundeza ímpar, e a marcha bélica do terceiro movimento com uma esperança aterradora. É ver pra crer.