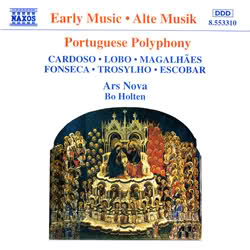

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony

The Choir of Westminster Cathedral

Até bem recentemente a música da Renascença Portuguesa jazia em quase completa obscuridade. Alguns compositores que haviam tido a sorte de ver suas obras publicadas em vida – caso de Manuel Cardoso, Duarte Lôbo e Filipe de Magalhães – já começaram a receber o reconhecimento que merecem, mas o mesmo não se aplica ao vasto corpus de música que permanece preservada apenas em manuscritos.

A maior coleção de tais manuscritos é de longe a que tem origem no mosteiro agostiniano da Santa Cruz, em Coimbra (Norte de Portugal). Esse mosteiro, casa materna da congregação agostiniana em Portugal, era um centro educacional e cultural de primeira categoria, com uma vida musical exuberante.

Mais importante dos compositores que trabalharam em Santa Cruz, Pedro de Cristo nasceu em Coimbra por volta de 1550 e tomou votos no mosteiro em 1571. Aí chegou ao posto de mestre de capela (isto é, de diretor do coro polifônico) na década de 1590. Dom Pedro também passou pelo menos dois períodos em Lisboa, como mestre de capela do Mosteiro de São Vicente. Um obituário que situa sua morte em 1618 menciona sua habilidade tanto como instrumentista quanto como compositor, e observa que seu talento musical o tornou requisitado por muitas das casas da congregação agostiniana.

As obras sacras de Pedro de Cristo – que passam de duzentas – dominam os manuscritos de Santa Cruz da década de 1580 à de 1620, sendo diversos deles da mão do próprio compositor. Muitos dos textos musicados refletem ênfases devocionais próprias de Santa Cruz. Um exemplo claro é o moteto Sanctissimi quinque martires, celebrando os “cinco mártires de Marrocos” – franciscanos que morreram em 1220 pregando aos muçulmanos ocidentais, cujas relíquias eram preservadas em Santa Cruz. Se essa peça apresenta de modo geral uma técnica contrapontística convencional, com frequência Dom Pedro empregava um estilo ritmicamente animado e de concepção mais vertical [em que as diferentes vozes se movem “nota contra nota”, prefigurando os conceitos mais tardios de “acorde” e “harmonia”] – o que se vê com especial clareza em suas musicalizações dos responsórios para as Matinas do Dia de Natal, bem como em obras para dois coros como o Magnificat no oitavo tom [faixa 15 nesta gravação] e a Ave Maria [faixa 14]. Nos responsórios de Natal cada unidade de sentido do texto é arranjada separadamente, com atenção meticulosa à acentuação correta, produzindo uma forma vívida de retórica musical.

Entre os outros compositores portugueses cujas obras estão preservadas nos manuscritos de Santa Cruz, um dos melhores é Airez Fernandez. Infelizmente ainda não se sabe nada de certo sobre a sua vida (embora seja provável que tenha atuado em Coimbra, possivelmente na Catedral), e não são muitas as obras atribuídas a ele que chegaram a nós. Sua musicalização da antífona mariana Alma redemptoris mater demonstra sua habilidade de produzir frases de maravilhosamente torneadas dentro de uma textura bem simples, sendo uma realização ainda maior pelo fato de que a voz do tenor segue quase estritamente a melodia gregoriana dessa antífona.

Owen Rees © 1991 Editions of the works by Pedro de Cristo and Aires Fernandez were made by Owen Rees.

Frei Manuel Cardoso nasceu em Fronteira, parte da diocese de Évora, em 1566 (embora antes se pensasse que em 1570). Fez votos de monge em Lisboa em 5 de julho de 1589. Segundo o Padre Manuel de Sá, foi “mandado a Évora para estudar gramática e a arte da música assim que teve idade para isso”, o que se julgou que fosse o caso aos nove anos, em 1575. Cardoso foi aluno aí dos padres Cosme Delgado e Manuel Mendes.

No decurso de sua carreira Cardoso viria a desfrutar do favor da Casa Real espanhola. Seu livro de missas sobre o tema Ab initio, de 1631, foi dedicado a Felipe IV. Esteve também ligado à família Bragança durante o tempo em que esteve no Convento Carmelita em Lisboa, e é provável que o futuro rei Dom João IV tenha sido seu aluno e patrono. Cardoso desfrutou de grande estima ao longo de sua vida tanto por sua vida piedosa quando por seus dons musicais excepcionais; foi frequentemente mencionado por seus contemporâneos de renome, tanto do campo musical quanto do literário, e era querido e respeitado por todos quando morreu em 1650.

Sobrevivem cinco coleções publicadas de obras de Cardoso: três livros de missas e dois volumes contendo Magnificats e motetos – porém dois dos motetos gravados aqui (Sitivit anima mea [faixa 2] e Non mortui [faixa 1]) foram publicados na verdade em uma das coleções de missas: a de 1625, que contém a Missa pro Defunctis. Os dois têm textos associados a ritos funerários. As outras obras gravadas procedem do volume de 1648, que foi a última publicação de Cardoso.

É característico de todas essas peças a combinação da escrita contrapontística ao modo de Palestrina (inclusive, as missas paródicas contidas no volume de 1625 de Cardoso são todas baseadas em Palestrina) com um modo muito pessoal de conduzir a harmonia. Os abundantes intervalos aumentados, entradas e progressões inesperadas e falsas relações, embora não exclusivos de Cardoso, são certamente mais evidentes na sua obra que na dos seus contemporâneos em Portugal, como Duarte Lôbo. Cardoso também escreveu música policoral – o que seria um meio mais óbvio para a aplicação de tais caracteríticas “barrocas” – mas essa foi toda perdida no terremoto de 1755, em Lisboa.

É a combinação dessas características com seu excelente conhecimento do contraponto palestriniano clássico que dá à música de Cardoso o seu caráter individual. Nos autem gloriae [faixa 5] ilustra bem o prodimento típico nesses motetos, que começam com um processo de imitação conscienciosamente elaborado (frequentemente a partir de três pontos, sendo a segunda entrada uma inversão da primeira), e então prosseguem de uma mandeira menos rigorosa, porém sempre com o máximo respeito na adaptação musical da palavra. No moteto Mulier quae erat [faixa 3] as inflexões cromáticas da elaboração imitativa inicial são tais, que não parece haver nenhuma tonalidade específica até que todas as entradas tenham acontecido e, por assim dizer, confirmado sua tonalidade uma com a outra.

Curiosamente, tais torções cromáticas não contradizem a serenidade transmitida por grande parte da música de Cardoso, trate-se de motetos ou de missas – e isso, poder-se-ia sentir, é de fato uma característica do barroco.

Além da Missa pro Defunctis, o exemplo mais resplandescente dessa “serenidade cromática” é provavelmente a que se encontra nas Lamentações. As destinadas à Quinta-Feira Santa [faixas 6 a 9] estão repletas de todas essas características encontradas nos motetos, e no entanto Cardoso nunca peca com algum exagero impróprio. A adequação litúrgica é respeitada sempre.

João Lourenço Rebelo nasceu em Caminha, na província do Minho, no Norte de Portugal, em 1610, 44 anos depois de Manuel Cardoso, embora tenha morrido apenas 11 anos depois deste. São desconhecidas as razões de haver mudado seu nome, pois era irmão de Marcos Soares Pereira, capelão-cantor na capela ducal [dos Bragança] em Vila Viçosa, o qual, quando aceitou tal nomeação, levou Rebelo consigo para que lá recebesse instrução musical. O patrocínio ducal (que mais tarde se tornou real) foi um elemento fundamental na vida de Rebelo, e ao que parece o próprio Dom João IV teria escrito dois motetos a seis vozes para completar uma das publicações de Rebelo (motetos dos quais resta somente a parte de uma das vozes).

A maior parte da música de Rebelo foi publicada em 1657, um ano depois da morte do seu patrono real, que deixou em seu testamento a ordem de que fosse impressa. Essa edição contém catorze musicalizações de Salmos (sendo duas séries de sete, cada texto musicado duas vezes), quatro Magnificats, música para as Completas [última das horas canônicas], duas Lamentações e um Miserere. O estilo policoral [então] moderno dessas obras fazem de Rebelo uma figura de considerável significação na história da música portuguesa. Há também um pequeno grupo de obras não publicadas para grupos menores, entre as quais se encontra o Panis angelicum [faixa 10].

Embora não possa ser descrita como policoral, Panis angelicum ilustra bem a música de Rebelo quanto a outros aspectos, ao usar um estilo melódico distintivo, às vezes fragmentário, com trechos de escrita homofônica ou perto disso. Talvez possamos ver aqui os últimos limites a que poderia chegar uma combinação de uma escrita contrapontística conduzida de modo genuíno com elementos de estilos mais novos. Nesse sentido, pode bem figurar como um emblema de Portugal nesse período, situado no último limite do continente e recebendo aí os ventos de mudança dos outros lugares da Europa da época.

Ivan Moody © 1991 Editions of the works by Cardoso (except the Lamentations) were made by Ivan Moody. The Rebelo piece was edited by Fr José Augusto Alegria and is published by Vanderbeek & Imrie Ltd, 15 Marvig, Lochs, Isle of Lewis, Scotland HS2 9QP

(Extraído do encarte. Traduzido do inglês pelo Prof. Ralf Rickli <[email protected]> especialmente para esta postagem. Obrigado!)

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony: The Choir of Westminster Cathedral

Frei Manuel Cardoso (Portugal, 1566-1650)

01. Non mortui

02. Sitivit anima mea

03. Mulier quae erat

04. Tulerunt lapides

05. Nos autem gloriari

Lamentations for Maundy Thursday ‘Feria quinta in Coena Domini’

06. – Responsory 1: In monte Oliveti oravit ad Patrem

07. – Lectio 2: Vau. Et egressus est a filia Sion omnis decor eius

08. – Responsory 2: Tristis est anima mea

09. – Lectio 3: Jod. Manum suam misit hostis ad omnia desiderabilia eius

João Lourenço Rebelo (Portugal, 1610-1661)

10. Panis angelicus

Dom Pedro de Cristo (Coimbra, c1550-1618)

11. Hodie nobis de caelo

12. O magnum mysterium

13. Beata viscera Mariae

14. Ave Maria

15. Magnificat

16. Sanctissimi quinque martires

Aires Fernández (fl.c.1590/1600 )

17. Alma redemptoris mater

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony: The Choir of Westminster Cathedral

Masterpieces of Portuguese Polyphony: The Choir of Westminster Cathedral

Director: James O’Donnell

Iain Somcock, organ

Celia Harper, harp

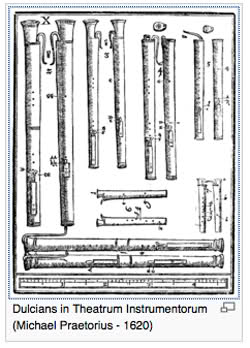

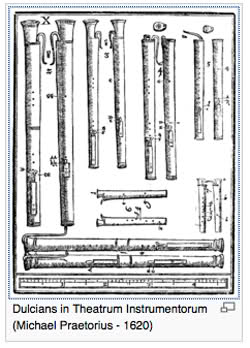

Sally Jackson, dulcian (11 – 15)

Recorded in Westminster Cathedral on 13, 14, 20, 21 June 1991

BAIXE AQUI – DOWNLOAD HERE (com encarte)

MP3 320 kbps – 161,8 MB – 1,1 h

powered by iTunes 12.1.0

Boa audição.

Avicenna

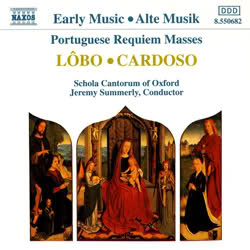

Missa de Requiem

Missa de Requiem

IM-PER-DÍ-VEL !!!

IM-PER-DÍ-VEL !!!