Cá estou eu, FDPBach, explorando mares desconhecidos, adentrando no século XX, com um pouco de resistência talvez, mas aberto à diferentes possibilidades e sonoridades, principalmente.

Cá estou eu, FDPBach, explorando mares desconhecidos, adentrando no século XX, com um pouco de resistência talvez, mas aberto à diferentes possibilidades e sonoridades, principalmente.

Primeiramente, permitam-me justificar minha ausência, ou presença pouco constante, desde as festividades de aniversário do PQPBach: problemas alheios à minha vontade, de ordem estritamente pessoal, tem me impedido de frequentar com mais frequência estas paragens, sobrecarregando assim meus queridos e estimados colegas, principalmente nosso mentor, PQPBach, e nosso Mestre Avicenna. Já expliquei a ambos os motivos e razões de minha ausência constante, e ambos, condescendentes e solidários, por que não assim o dizer, têm se esforçado a cobrir a parte que me cabe neste latifúndio. mas tenho ouvido muita música, podem ter certeza. Esta faz parte de minha vida, e assim o será, até o final de meus dias.

Mas comentei acima que com esta postagem estou adentrando em mares nunca dantes navegados. Creio que até ter acesso a este cd recém lançado do selo Pentatone, nunca antes havia ouvido alguma obra de Martinu. Mas os sobrenomes dos intérpretes me chamaram a atenção: tanto o das irmãs Kodama, Mari Kodama é uma grande intérprete de Beethoven, e as irmãs Nemtanu, conhecia apenas a Sarah.

A proposta do CD é interessante: obras compostas para dois instrumentos, a saber, Piano e Violino, e as solistas são irmãs. E ainda temos uma Rapsódia para Viola e Orquestra, para alegria de nosso colega Bisnaga, que confessou entre nós ser ser um violista amador. A modéstia o impede de nos dar uma palhinha, mostrar todo o seu talento. Sabemos também que sua rotina de trabalho é exaustiva: vida de professor não é fácil.

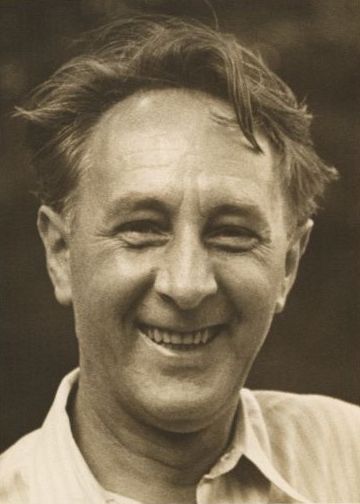

Mas chega de falar bobagem: apresento então para os senhores Boheslav Martinu, nice to meet you, too. O texto abaixo foi retirado do booklet do CD:

An Undogmatic Nomad

Thoughts on Concertante Works by Bohuslav Martinů

“A slice of heaven is revealed in each of his pieces.” This wonderful and eloquent sentence was once uttered by Bohuslav Martinů’s wife, Charlotte. It set the tone for music that had been exposed for decades to an abundance of extremely heterogeneous influences and role models, ranging from Honegger, Stravinsky and Neoclassicism, through jazz, to English madrigals. However, this is music that not only sought its own path, but definitely found it. Music that, thanks to its daring individuality and courage, has finally earned its place in the limelight. For Martinů is undoubtedly one of the most important composers of the 20th century; and his numerous and extremely diverse works are still capable of stirring us in the 21st century, as members of an insecure society that is continually questioning the key challenges facing humanity. And to which Martinů gave a foresighted answer back in 1956: “The artist is always searching for the meaning of life, both of his own and of that of the human race; searching for the truth. A system of insecurity has invaded our everyday lives. We must protest against the pressure to favour mechanization and uniformity to which our daily life is subjected; and the artist has only one means of expressing this – in his music.”

The eternal emigrant

Martinů led an adventurous life. Born on December 8, 1890 in Polička, Bohemia, he received a scholarship to enter the Prague Conservatoire at the age of 16, where he studied the violin. However, his years of study – which later included both organ and composition – did not

constitute a glorious chapter in his life; he was not content to keep to academic rules and regulations and was expelled from the conservatoire in 1910 for “incorrigible negligence.” Nevertheless, in 1912 he managed to graduate at his second attempt. During World War I, Martinů was exempted from military service, and returned to Polička to teach the violin. In 1920, he became a violinist in the most important Czech orchestra – the Czech Philharmonic.

His first compositions were a success, and in 1922 Martinů entered Josef Suk’s composition class. However, just one year later, he set off to Paris with a travel grant in his pocket in order to continue studying composition under Albert Roussel – and to seek new impulses. His stay there, which was originally planned for three months, finally turned into 17 years. Following initial difficulties, this was a highly successful period for Martinů: many of his works were also performed in international concert halls; he received a number of awards; and his artistic career was followed with interest by influential conductors, including Paul Sacher. He also found happiness in his private life after marrying a French woman, Charlotte Quennehen. Martinů had a good reputation in the world of music; but in June 1940, the happy days in Paris came to an abrupt end. When the German Wehrmacht invaded France and occupied Paris, Martinů was forced to flee across southern France, Spain and Portugal to the USA, where he and his wife finally ended up in March 1941. This proved to be a wise decision, as the Nazis issued a performance ban on his works shortly after invading Czechoslovakia. Martinů was able to take only four of his manuscripts with him, the rest he was forced to leave behind in Paris.

Thanks to his contact with Serge Koussevitzky, the composer quickly established himself in his new home. He settled down to write a total of six symphonies and, above all, numerous concertos, including the Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra H. 292, the Concerto for Two Violins and Orchestra H. 329 and the RhapsodyConcerto for Viola and Orchestra H. 337. Thus the recording at hand provides a concentrated overview of Martinů’s activities as a composer in the United States. Yet all these artistic achievements were able only to assuage his homesickness, not to resolve the problem. Plans for a return to the Czech Republic after the war ended were scrapped due to political reasons, and a serious accident at the Berkshire Music School left Martinů with serious consequences for the rest of his life – he was left deaf in one ear and suffering from balance issues. When he journeyed to Europe in 1948, he decided not to visit Czechoslovakia as the communists were now in power in his country. In the early 1950s, Martinů dedicated himself once again to composition; and in 1952, he became an American citizen. Nevertheless, the following year he finally turned his back on his adopted country to return to Europe. After first sojourning in France and Italy, he accepted an invitation from Paul Sacher to settle on his estate near Basel, where he finally died on August 28, 1959. A life-long emigrant on an artistic quest, he was never able to completely tear himself away from his homeland.

The quester

In his works, Martinů continued in the great Czech traditions as set out by Smetana, Dvořák, Fibich and Janáček – albeit under his own steam. He was a truly prolific composer, writing more than 400 compositions, including 31 concertos and concertante works; a prolific writer of high quality, who composed with great speed, absolute stylistic command, and above all with undogmatic creativity. The BärenreiterVerlag is in the process of publishing a historical-critical complete edition, which will finally comprise about 100 volumes. As the publishing situation is highly complex in Martinů’s case, this also marks a decisive milestone with regard to the world-wide diffusion of his œuvre, as “many works are available only in inadequate first editions of over 50 years old, many of which include unauthorized editing. Some works were never even properly typeset; instead, they were distributed by the publishers in transcriptions, or even in the form of reproductions of the composer’s rather illegible manuscripts” (Bärenreiter website).

Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra H. 292

The 20th century saw the emergence of a number of outstanding works for the unusual combination of two-piano concertos, created by great composers such as Francis Poulenc, Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky. Martinů composed his Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in a very short period of time, from January 3 to February 23, 1943. As he stated: “I have used the pianos for the first time in the purely ‘solo’ sense, with the orchestra as accompaniment, the form is free; it leans rather toward the concerto grosso. It demands virtuosity, brilliant piano technique and the timbre of the same two instruments calls forth new colours and new sonorities.”

Mari Kodama agrees that the piano parts provided by Martinů are extremely difficult – and not only for Genia Nemenoff and Pierre Luboschutz, the pianists who commissioned the work and gave the world première in Philadelphia on November 5, 1943: “As a pianist, you really need to be highly concentrated in order to understand the complexity!”. Influenced by the Baroque concerto grosso (as in his Concerto for Two Violins and Orchestra H. 329), Martinů deploys the orchestra as a counterpart to the two pianos. The first movement is a rhythmic and pianistic tour de force, during which both pianos are almost permanently on the go: high-speed toccata fireworks. The slow middle movement is introduced by a cadenza that Mari and Momo Kodama acknowledge as possessing a well-nigh “cutting irony”. As it contains very few bar line indications, all solo instruments have a great amount of freedom. After this haven of tranquility, the brilliant Rondo finale once again sets lashings of local musical “dust” aswirl. Hartmut Becker even remarked on a “tendency to emphasize the Czech atmosphere”. To quote Martinů: “The work was written under terrible circumstances, but the emotions it voices are not those of despair, but rather of revolt, courage and unshakable faith in the future.”

Concerto for Two Violins and Orchestra H. 329

Martinů wrote the concerto between May and June 1950 following a commission from the twin prodigies, Gerald and Wilfred Beal, who were subsequently the soloists at the première in Dallas on January 14, 1951. Despite the large-scale orchestra required for this work, the concertogrosso style is ever-present. The three-movement concerto thrives on the extraordinary virtuosity of the solo instrument parts. In the first movement, dashing runs and highly complex double-stops, which increase even to quadruple-stops, raise the bar to extreme heights, expanding the sound space considerably. In the middle movement, the two soloists alternate the melodic leadership. The euphonious music of the final movement once again gives the solo violins the opportunity to fully display their virtuosity.

Rhapsody-Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, H. 337

In his viola concerto, Martinů distances himself from the echoes of the concerto grosso form. He wrote the composition, which was commissioned by the Ukrainian violist Jascha Veissi, between March 15 and April 18, 1952. This work again demonstrates how Martinů managed to cater to the individual wishes of his “clients”. The piece demands virtuoso playing, without making any sacrifices in substance.

As the composer himself later stated, he went through a development that led him away from “geometry” in the direction of “fantasy”. To quote the great Martinů-expert, Aleš Brezina, here “his ability to build up extensive lyrical passages ending in strong catharsis reaches its first peak.” The two-movement work is characterized by inner peace and modesty; harmonic oscillation and simple melodies go hand in hand. In the compelling conclusion of the concerto, Martinů returns with the listener to his own childhood, when he “used to march around the gallery of the church tower in Polička, drumming away on his small drum”. The artistic nomad is finally settling down. And a slice of heaven is revealed to the listener.

Martinů Double Concertos

01. Concerto No. 2 in D Major for 2 Violins, H. 329 I. Poco allegro

02. Concerto No. 2 in D Major for 2 Violins, H. 329 II. Moderato-III. Allegro con brio-Vivo

Sarah Nemtanu & Deborah Nemtanu – Violins

Orchestre Philharmonique de Marsaille

Lawrence Foster – Conductor

03. Rhapsody-Concerto, H. 337 I. Moderato

04. Rhapsody-Concerto, H. 337 II. Molto adagio-Allegro

Magali Demesse – Viola

Orchestre Philharmonique de Marsaille

Lawrence Foster – Conductor

05. Concerto for 2 Pianos, H. 292 I. Allegro non troppo

06. Concerto for 2 Pianos, H. 292 II. Adagio

07. Concerto for 2 Pianos, H. 292 III. Allegro

Mari Kodama & Momo Kodama – Pianos

Orchestre Philharmonique de Marsaille

Lawrence Foster – Conductor

Martinu é um dos monstros do século XX. Teve o raro dom de combinar música muito bem elaborada e extremamente agradável de ouvir. E ainda por cima tinha bom humor – uma de suas obras é uma cantata em homenagem à fumaça de batatas queimando.

Não tenha mêdo, FDPBach, os portugueses já desbravaram esses mares pra você!!!